Bachelor of Arts History & Politics

Diploma of Professional Writing & Editing

Ken Purdham

ETU Vic historian

Now my working life has come to an end and I look back in many ways it was my working life that defined me. It influenced the way I think, the way I am. My experiences and memories of my working life are many and it began when I walked out of one school and into another in September 1965.

The Apprentice School

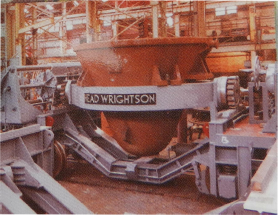

I left school in September 1965, one month before my sixteenth birthday, and went to work as an apprentice at a heavy engineering firm called Head Wrightson’s. How exciting for me; no longer a school kid, I was working!

On my first day at the HW apprentice school, I sat, wide eyed, with fifty other new

apprentices, face to face with ancient looking, silver-

We’d be going out to different sites for work-

There was a safety officer who’s message wasn’t lost on me, though. He was a bloke who had one hand missing and he wore a brown shiny leather glove on a false fist. He knew frst hand, they told us, the price to pay for poor safety practices . Throughout my apprenticeship he’d turn up unannounced and cast his critical eye over the workshop. And he was feared by all because he had power. His word was law! When he waved that false fist at something he didn’t like, well, the memory of it still makes the point of what safety was all about.

Finally, they said, at the end of our six months in the apprentice school we’d be assessed and offered an apprenticeship in that trade at which we’d shown the best aptitude.

So, with that, I began my working life going out to the various sites; a new kid

in crisp, never worn before overalls that were stiff and too big for me; while on

my feet I wore shiny steel-

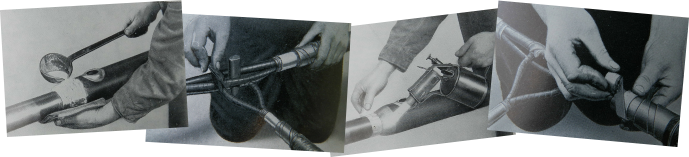

I wanted to be an electrician and spent a week with a couple of cable jointers. It

was winter and they were working in a muddy hole, down by the river, joining a big

cable together. I had no idea what was going on but remember them carefully binding

each core of this big cable with a kind of cloth tape before using a blow torch to

melt lead and form it with a thick lump of leather, into a knuckle around the joint

they’d made. It was clear, squatting in a muddy hole for a week, with freezing feet,

and melting lead with a blow-

It was then on to the toolmakers shop. The toolmakers were the elite of the trades.

Anyone who wanted machine cutting tools and drills sharpened brought them to the

toolmakers. From there to the fitters and turners, watching them fitting and setting

up whatever they were putting together, with micrometers, steel rules and set-

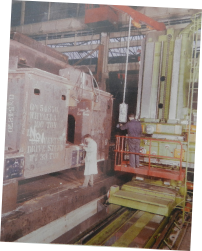

From there it was into the fabrication workshops where I watched boilermakers use

a chalk line to mark giant plates of steel, then with an impressive rhythmical action

put a series of pop marks along the chalk line with their centre-

My Uncle John was the forman in the pattern makers’ shop and there I saw the pattern makers make wooden patterns destined for the founderies. They were like wooden sculptures to me. Sitting with my Uncle as he filled in my report book at the end of my week, is the warmest memory I have. He made me feel good about the start of my working life.

So, what do you know, when I went back in the apprentice school workshop and the

ancient grey coats, they told us we were going to make a centre-

Right then, to make my centre-

For my set-

After fifty-

With my center-

And so I entered my new world as a factory worker in heavy engineering, where for the next five years I progressed through my apprenticeship forging memories that have lasted me a lifetime.